Or: Connected thoughts on art and politics from May & September 2023

1. Listening to Tuareg guitar while enjoying dinner

Around May last year, like Mole, I was spring cleaning. From a stack of magazines, I stopped to re-read an issue of The Wire from 2019, which has a great feature on Tuareg Guitar or Desert Blues: that genre of North African rock music made globally famous by Tinariwen.

I remember first hearing Tinariwen when they came to European prominence around 2004. Andy Kershaw, recently farmed out from Radio 1 to Radio 3 at the time, definitely played them, and I have a grainy VHS tape of their performance at Womad 2004 that was broadcast on BBC television. Imagine that. Of course my VHS is (thankfully, I suppose) made redundant by the appearance of the concert on ‘youtube’ (complete with typically laughable BBC intro montage):

At the time, Tinariwen were heralded in the press as the vanguard of an entirely new style of rock music: a pulsing rhythmic repetition and wiry guitar sound, like a north African Velvet Underground. I didn’t delve much deeper than that myself.

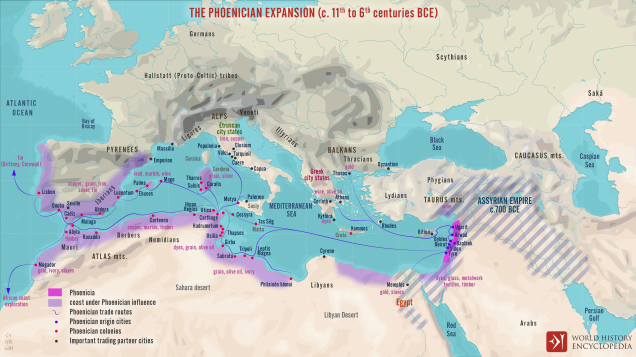

The introduction to the Wire article (by Francis Gooding: ‘The Primer: Tuareg Guitar’, The Wire 420, February 2019) explains the political situation that Tuareg Guitar groups emerged from. The history dates at least to 1963, taking in the various roles of French neocolonialism, Gaddafi, al Qaeda, Islamic State, American drones and uranium mining. The armed role of key Tuareg musicians in rebellions and the struggle for political recognition feeds into the legends and mystery surrounding Tinariwen and their peers.

Gooding did a good job of contextualising the origins of the music, while focusing mainly on the music itself. The article judged well the line that sometimes writing about Tuareg Guitar makes a proper mess of. So often we hear picturesque anecdotes about musicians putting down their guns to pick up their guitars before going on stage, packaging a Romantic legend of the freedom fighter for our consumption.

Teshumara: Les guitares de la rébellion Touareg, dir. Jérémie Reichenbach, 2005

I’m certainly not qualified to comment on a political situation I know more from LP sleeve notes than from anything else. From the comfort of my desk, there’s undeniably an unease in the vicarious pleasure I derive from listening to the authentic voice of armed struggle (although these days, the recordings are often augmented by American or European musicians). Or perhaps the unease is part of the pleasure? The disjuncture is most acute if, say, you put the record on to accompany your dinner, then put the fork down to read the translated or annotated lyrics. And suddenly the roasted vegetables are thrown into the traumatic memories of death, war and exile.

At the same time, I recognised this queasiness as the useless handwringing of the comfortable. Shouldn’t we just enjoy the fierce riffs, cresting rhythms and the voices that communicate across language barriers? I suspect that the aestheticisation or fetishisation of songs of sorrow is an ancient process.

Bombino performance outside the Grand Mosque in Agadez (a video recommended in Gooding’s article).

2. Tuareg, Tyrians and Romans and epic

The myths of Carthage, as told by Romans such as Vergil, incorporated post hoc justifications of the Punic Wars (3rd – 2nd centuries BCE) which ended with the total destruction of Carthage and the subordination of Phoenician settlements to Rome in 146 BCE. And it is war that is famously, synecdochally invoked by the first word of the Aeneid: arma (variously translated ‘weapons’, ‘arms’, ‘war’, ‘warfare’). Equally famously, Vergil is following Homer’s thematically-loaded first words of the Iliad and Odyssey.

War drenches the language of epic poems. One theory goes that the Homeric poems were developed in an oral tradition during the Ancient Greek ‘Dark Age’, c. 1200-800 BCE. As with other Dark Ages, it simply connotes a loss of a written record, as the people who wrote Linear B died or were enslaved or driven into exile, or whatever else may have happened during the so-called ‘Bronze Age Collapse’. So we imagine the bards singing songs of the heroes of the previous generation, of wars and palaces, of divinely-gifted warriors, cannibal giants, sea monsters and geo-political upheaval across the Aegean. When did these authentic songs of first-hand-experienced trauma and loss become aestheticised and fetishised? As soon as Homer’s poems appear in the written record, they are already aesthetic objects. They may have had roots, once, like the Tuareg Guitar, in real conflict, but they were transplanted out of their immediate historical context, becoming generalised poems of war, rage, quest and nostalgia. If the songs ever told of material reality, we only know their mythical reality.

3. Political art in times of crisis

This all came to mind in the context of the UK’s political situation: observable on the high street, where once-indominable chain stores become vast boarded-up palaces of void, as the holders of the highest offices of government continue to use the country as a cash machine for themselves and their already-unspeakably-wealthy friends and contacts, where every GP appointment carries with it the fear that it will be the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Surveying this managed decline from above is the dispassionate eye of the media class. Perhaps it was around 2019 when I began to notice this: comfortable liberal journalists pitching articles in the press about how times of political hardship are good for the culture. The argument goes that regressive politics inspires fiery, impassioned, and thrilling music, comedy, theatre and art. If I could be bothered spending ten minutes with The Grauniad‘s search engine I could probably find one for you. Commentary of this sort explains the wider phenomenon of the patrician coolness of the press when reporting times of crisis: they are personally insulated from the sharpest edges of political power. And it helps explain why, in 2019, despite all the bluster, the seemingly ‘left of centre’ ‘legacy media’ feared the loss of charitable status for private schools much more than they feared ‘brexit’, and why, with the clubbable and purchasable Sir Kid Starver as opposition leader, they’ve all calmed down. Still, as I noted in July 2022, you can say what you like about Starmer, at least you know what you’re going to get from him. He looks like a plastic bag of offal pressed into the shape of a frightened little boy and pushed into a suit, and he’s got the principles of a plastic bag of offal pressed into the shape of a frightened little boy and pushed into a suit.

The media commentators were wrong about the art, as well. It’s toothless as ever. I enjoyed the recent Sleaford Mods album, but from a political point of view, it’s just whinging. There’s some comfort of solidarity in realising that other people can see the same things you can see, but I’d rather had a fully-funded health service and a halt to fossil fuel expansion.

It’s a Romantic cliché that great art comes out of great suffering. Even in Classical Athens it probably isn’t quite true. Aeschylus certainly had first-hand experience of combat in the Greco-Persian wars, but Sophocles, by all accounts, had a comfortable life, and yet he composed tragedies of the most harrowing psychological insight. Nevertheless, suffering may accelerate or catalyse the process. And if we then derive pleasure from the product, is there any harm?

4. Art in and out of context

Another legend, told by Cicero, c. 55 BCE, says that it was Peisistratos, the tyrant of Athens in the sixth century BCE who commissioned authoritative written editions of Iliad and Odyssey. Is this Cicero’s early-Roman Empire back-projection, imagining that the Archaic Greeks were as desirous of a nationalist epic as Augustus was soon to find in Vergil’s Aeneid? Even if the “Peisistratid Recension” is mere fable, it fits with the supreme importance that Homer had for the Classical Greek imagination.

There is no art pour l’art: art absorbs the material conditions of its creation, and it endlessly radiates its spiritual product into the worlds that receive it. If Homer’s epics transcend the specificity of their creation, it’s not necessarily because the concerns are eternal, but because they are mutable.

5. P.S.

Belatedly typing this up as February turns to March 2024, here is the ferocious new song from Nigerian shredder Mdou Moctar, which mixes the Tuareg style with influences (as cited in Gooding’s article) from Hendrix, Prince and Van Halen. ‘Funeral for Justice’.